The Eternal Enigma of the Nsude Pyramid Shrines

Nigeria’s landscape harbours secrets that speak of vintage brilliance, and one of the most fascinating is the Nsude Pyramid Shrines.

Concealed in the Udi highlands of Enugu State, these remarkable buildings are testaments to the architectural as well as spiritual sophistication of the Igbo.

Unlike their ancient Egyptian counterparts, hewn from stone, these pyramids were constructed from the earth itself, forming unique circular, stepped shrines that held deeply spiritual meaning.

Their story is one of cultural brilliance, colonial discovery, and one of sad competition against time as they fade back into the country from which they came.

Table of Contents

Discover the Nsude Pyramid Shrines

The first known written records of the Nsude pyramids date back to early 20th-century Western observers, although their existence had been known to the local community for generations.

British missionary and ethnographer George Basden provided some of the earliest ethnographic accounts in his research circa 1912.

Read Also: The Majestic Ancient Kano City Walls: A Historical Icon

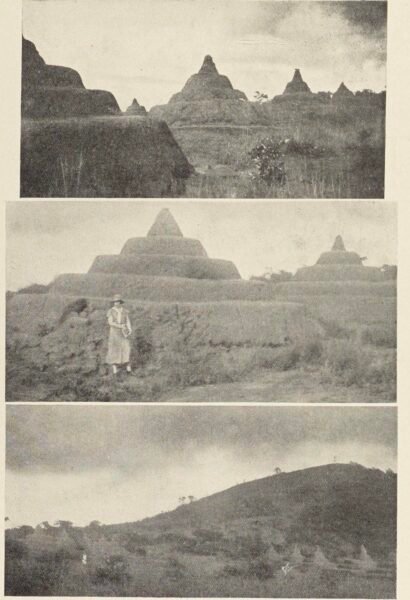

Most significant of all, however, is the photograph evidence taken in the 1930s by British colonial administrator and anthropologist G.I. Jones. His stark black-and-white photos, taken with a Rolleiflex camera, form the classic proof of these buildings as they existed in nearly pristine condition.

They were part of numerous photographs shot for a project to document the diverse cultures of southeastern Nigeria, inadvertently recording a legacy that would later fade away.

Nsude Pyramid Shrines Architecture

The construction of the Nsude pyramids was a feat of indigenous engineering. Using a method known as “walling,” builders created a series of circular tiers from hardened red mud and clay.

The process began with a circular trench, upon which layers of earth were progressively added, each new tier smaller than the last. This yielded a typical conical, stepped pyramid.

The foundation of the building began at approximately 60 feet in diameter, and every following level diminished in size down to the top.

The construction material, consisting of earth, clay, and most likely organic binders, was rammed and consolidated for stability, indicating an excellent understanding of local materials and environmental adaptation.

Nsude Pyramid Shrines Facts

These ten pyramids were not ego monuments or tombs, but living instruments of faith. They were constructed by the Nsude people, and each shrine was dedicated to Ala, the earth goddess, through the veneration of a localised divinity: Uto-Nsude, a war hero deified.

Guided by the vision of a Dibia, the people knew that Uto himself had requested ten buildings to be erected in his honour, and in a massive community effort, every one of the village’s ten quarters built a pyramid. At the pinnacle of every structure, a single small stick was placed, marking the precise dwelling point for the deity’s presence.

This straightforward but compelling symbol transformed the pyramids into sacred portals. They were rendered the centre of vital community ceremonies, offerings, and rituals, physically connecting the people with the divine and consolidating a shared spiritual identity.

Nsude Pyramid Shrines as Social Pillars

These structures were far more than spiritual centres; they were the bedrock of Nsude’s social unity. Building them was a unifying communal project that actively involved the ten extended families.

Their deliberate arrangement is the most telling clue. The two parallel rows, each containing five pyramids, directly echoed the village’s own dual-row layout. This was not a coincidence.

Read Also: Iho Eleru Skull: Ancient Human Fossil From Nigeria

Through the translation of their social organisation into the sacred geography, these cultures asserted their communal obligations and identity in a tangible, everyday manner. The pyramids were not only works of architectural beauty, but they were a celebration of the extent of their combined abilities.

Each citizen volunteered for this holy work not as a compulsory duty, but as an acknowledgement of their shared heritage and wholeness. This tradition created a foundation of mutual cooperation and shared endeavour; values not theoretical constructs but living realities woven into the fabric of their own everyday lives.

Nsude Pyramid Shrines’s Age

The actual age of the Nsude pyramids remains a mystery, as scientific dating methods have not yet been employed. This gap presents a thrilling mystery at the heart of their story.

Their appearance on stage, with a stepped series of levels, caused some commentators to notice a visual resemblance to the pyramids of Sudan and Egypt from ancient times. That is an interesting observation: were they an independent local innovation, or an ubiquitous, common African architectural motif?

We can never know. The master builders’ identity, too, is lost to history. Their advanced knowledge was passed down from generation to generation in practice, not in writing, so their individual techniques and tales remain untold. The pyramids remain great, but silent, witnesses to a bygone era.

How Nsude Pyramid Shrines Were Built

The construction methods of the Nsuke pyramids remain a testament to the lost engineering skills of the past. We know the basic technique was “walling,” a process of building concentric clay rings upwards.

Yet, the precise knowledge that granted these earthen structures their incredible longevity is still unclear. How did builders achieve such perfect symmetry and enduring stability using only simple tools?

The specific, sophisticated recipes for their clay mixtures and the meticulous compaction methods that defied centuries of erosion are details that have not been fully recovered.

This gap represents a profound loss of indigenous African technological knowledge. The builders’ intimate understanding of their local materials and environment has, sadly, faded with time, leaving us with a magnificent but silent mystery.

The Fading Legacy of the Nsude Pyramids

The Nsude pyramids’ history is a tale of cultural caution. Made of clay and laterite, materials naturally vulnerable to the depredations of a tropical climate, the pyramids have endured constant tropical rains and decades of abandonment. The definite, stepped terraces that archaeologist G.I. Jones surveyed in the 1930s have since dissolved mainly into the background.

Now, faint, overgrown mounds are all that can be found where these unique shrines stood. This deterioration began during the colonial era and has continued ever since, with minimal measures taken to preserve what remains.

Their loss is not merely physical, but the silent devastation of a singular architectural and spiritual achievement, a ghostly reminder of how cavalierly history becomes invisible when it is abandoned.

A Future for the Nsude Pyramids

A persistent push for preservation continues, driven by local community leaders and dedicated historians. Their goal is to reverse the decay and secure recognition for this unique site.

Proposals include widespread archaeological excavations to finally document the pyramids’ entire history and meticulous reconstruction using ancient, original methods.

This is not simply a matter of rebuilding structures; it’s a real thrust to recover a significant portion of cultural heritage. There is potential for gentle educational tourism, which could provide economic benefits to the region without eroding the site’s significance.

The most challenging hurdles, however, remain imposing ones: securing ongoing funding, expert personnel, and the essential political will to see this delicate project through with the respect and accuracy it so greatly warrants. The path is hard, but the determination is steadfast.

The Enduring Legacy of Nsude

The Nsude pyramids stand as a potent image of pre-colonial African excellence. They strongly contradict the old tales that once portrayed the continent as lacking in spiritual and architectural sophistication.

Read Also: Iyake Lake: Nigeria’s Breathtaking Hidden Natural Wonder

These structures serve as a grim reminder that advanced, high-tech traditions evolved in isolation across Africa, each tailored specifically to its indigenous environment and dominant cultural ethos.

To the Igbo, pyramids were indeed a true manifestation of a deep identification with their fatherland, their god Uto, and their Igbo heritage. Their history is not only a history of the past, but a valuable lesson for today.

The transitory nature of such shrines requires a global, immediate appeal: we must preserve the singular emblems of our shared humanity before they pass forever into the ages, their inestimable histories lost to the world.